(Part 3 of 3)

By Sunkanmi Adewunmi

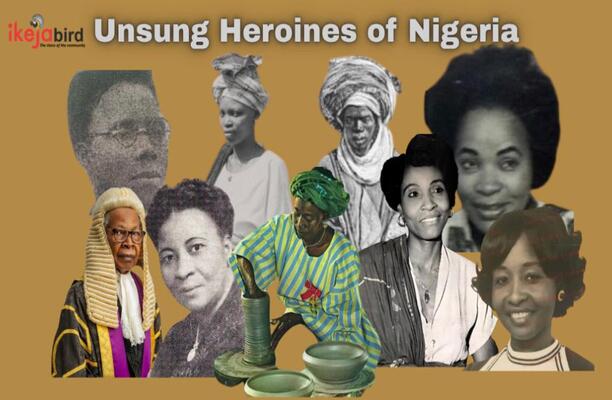

Welcome to the Final Part of Our Unsung Heroines Series

As we wrap up this series, we honour more incredible Nigerian women whose quiet strength shaped history. Their names may not be loud, but their impact is lasting. Let their stories inspire you to lead, create, and rise just as they did.

Chief Dr. Elizabeth Abimbola Awoliyi (1910–1971) earned the title “Dr. Mrs. Awoliyi” across Nigeria but few know her true pioneering story. Born in Lagos to Aguda (Brazilian-returnee) parents, she was educated at Queen’s College Lagos and became one of the first Nigerian women ever sent abroad for medicine. In 1938 she graduated from Trinity College Dublin with first-class honors and won a licence from the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland becoming the first West African woman surgeon-qualified doctor. By 1959 she was back in Nigeria as Chief Consultant Gynecologist and Obstetrician at Massey Street Hospital, eventually serving as medical director there.

Awoliyi’s contributions went beyond the clinic. She was a leader of women’s organizations and public health. From 1964 to her death she was president of the National Council of Women’s Societies, mobilizing women’s groups nationwide. She also ran a poultry farm and medical supply business, a female entrepreneur at a time when few women had bank accounts or farms. In recognition, she was honoured with Nigeria’s Order of the Federal Republic and became an Officer of the British Empire (MBE) for her service.

Dr. Awoliyi’s story shows that dedication and education can break glass ceilings. Her life encourages women to aim high in STEM fields and public service, proving that barriers can be overcome one goal at a time.

The Trailblazing Hairat Balogun

Hairat Aderinsola Balogun (born 1941) is rightly called a “woman of many firsts” in Nigeria’s legal profession. Daughter of a prominent Lagos family, she left for England as a child and was called to the English Bar at age 21 in 1963. Upon returning, she quickly shattered glass ceilings: in 1981 she became the first female Secretary-General of the Nigerian Bar Association, and later (1989–1999) the first woman Bencher and first female Chair of the Body of Benchers. Her crowning achievement came as Lagos State’s first female Attorney-General (later Director of Public Prosecution), a role in which she helped shape Lagos’s laws and mentored young lawyers. She even served as President of the Lagos Rotary Club (2012), the first woman in that role.

Despite all this, Balogun’s name rarely comes up outside legal circles. The achievements of modern celebrity judges or politicians often overshadow senior legal minds. Yet Balogun’s legacy is inspiring: she earned an Officer of the Order of the Niger (OON) honor and wrote memoirs (“To Serve in Truth and Justice”) that offer guidance to future lawyers. She exemplifies professionalism, dedication and breaking gender barriers. In her own words during interviews, she emphasized fulfillment through service. “I am completely fulfilled,” she once said, reminding women that a career itself can be deeply rewarding.

The Legacy of Charlotte Obasa

Charlotte Olajumoke Obasa (1874–1953) was a Lagos socialite who quietly revolutionized her city. Daughter of wealthy merchant R.B. Blaize and wife of Dr. Orisadipe Obasa, she used her privilege to pioneer entrepreneurship and philanthropy. In 1907 she contributed to the establishment of the Lagos School for Girls (later Wesley Girls’ High School) by lending her property for the school, ensuring young Nigerian women could get a formal education. But she didn’t stop at education. In 1913 she founded Lagos’s first transport service called the Anfani Bus Service with trucks, taxis and buses easing transport in the growing city.

Obasa’s life was one of “firsts”: she co-founded the Reformed Ogboni Fraternity in 1914 and became its first female leader (Iya Abiye). She also supported war relief during World War I and funded civic projects, embodying a true community philanthropist. Despite these achievements, Obasa remains largely unknown today. Mainstream narratives tend to forget early 20th-century women entrepreneurs. Yet, as one article notes, she “proved women could do it all” running businesses and services that modernized Lagos.

Her story is inspiring, here was a woman who broke gender norms to run a transport company and champion girls’ education long before Nigeria’s independence. Obasa’s determination, from classrooms to city streets, offers a powerful lesson in vision and service.

Each of these stories celebrates Nigerian women whose legacies deserve to echo far and wide. They remind us that history isn’t solely written by presidents or monarchs, it’s shaped by market women, educators, doctors, and creatives who changed lives in powerful ways. Let their journeys inspire you. Your efforts, loud or quiet, matter. Believe in your voice, walk boldly in your truth, and continue the legacy of these extraordinary, unsung heroines.