(Part 1 of 3)

By Sunkanmi Adewunmi

Women have always been the heartbeat of Nigeria’s progress—nurturing communities, driving innovation, and breaking barriers. From grassroots activism to excellence in healthcare, art, and commerce, their impact runs deep.

While icons like Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti and Madam Efunroye Tinubu are rightly celebrated, many equally remarkable women remain overlooked. This article shines a light on unsung heroines whose powerful contributions have shaped Nigeria’s story. Whether as trailblazing doctors, bold activists, or creative pioneers, these women show us that legacy isn’t always loud, but it is lasting.

The Story of Alimotu Pelewura

Alimotu Pelewura (c.1865–1951) rose from humble beginnings as a Lagos fish trader to become one of Nigeria’s most formidable women leaders. Born into a polygynous family in Lagos, she followed her mother’s trade and by 1910 had earned a chieftaincy title under Oba Eshugbayi Eleko. By the 1920s she was head of Lagos’s Ereko market. Under colonial rule, Pelewura co-founded and led the Lagos Market Women’s Association, advocating fiercely for market women’s rights. She led massive protests against punitive colonial taxes on women in 1932 and again in 1940, personally marching with hundreds of women to demand relief. When colonial authorities tried to relocate her beloved market in the 1930s, she even went to jail only to be freed amid an outpouring of solidarity from market women.

Pelewura’s contributions were revolutionary: she built a powerful women’s union called the Lagos Market Women’s Association (LMWA) in the 1920s, challenged unjust economic policies, and stood shoulder-to-shoulder with prominent nationalists like Herbert Macaulay. Yet outside Lagos history circles her name is little known today. She is “unsung” partly because market women’s activism has often been overlooked by male-centered history. Still, her life brims with inspiration. Pelewura’s story reminds us that ordinary beginnings don’t limit one’s impact.

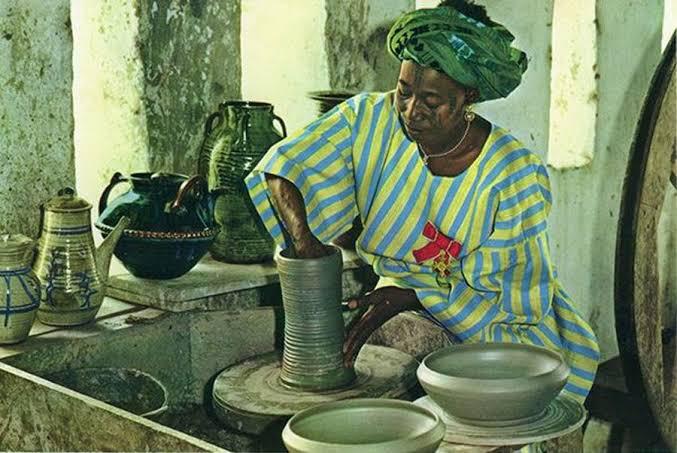

Ladi Kwali, Pioneer of Nigerian Pottery

Ladi Dosei Kwali (c.1925–1984) turned traditional craft into international art. Born in a village of potters near Abuja, she learned pottery from her aunt as a girl. In the 1950s, Michael Cardew, a British potter working in Nigeria, discovered her remarkable talent and brought her to the Pottery Training Centre in Abuja in 1954. There Ladi Kwali became the centre’s first female trainee and blended her free-hand Hausa/Gbagyi coiling techniques with new stoneware glazes. The result was a bold new style: heavy clay pots inscribed with patterns of fish, snakes and lizards, finished with celadon and other glazes. Her work “pioneered African ceramic art modernism,” blending age-old forms with modern aesthetics.

By the late 1950s she was exhibiting worldwide. London galleries (Berkeley, V&A) displayed her pots in 1958–1962, garnering international acclaim. She was awarded the Most Excellent Order of the Federal Republic by Nigeria, and today she is one of only three women depicted on African currency. Her image graces the 20 Naira note. Yet many Nigerians (especially younger generations) know little of her name or story.

Her inspiration lies in her artistic journey. She took the humble craft of rural women potters and elevated it to national heritage. She showed that creativity has value on par with science or politics. Ladi Kwali’s life is a vivid example that even traditional skills can achieve global recognition.

Adaora Lily Ulasi, Nigeria’s Literary Pioneer

Adaora Lily Ulasi (1932–2016) was one of the first Nigerian women writers in English, forging a literary path in the 1960s and ’70s. Born in Aba, Eastern Nigeria, daughter of an Igbo chief, she earned a B.A. in Journalism from the University of Southern California in 1954. Returning home, she became the Women’s Page Editor for the Daily Times (1954–56) and later editor of Woman’s World magazine in 1972. Ulasi also worked as a broadcaster with the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation and even the BBC when abroad.

Yet Adaora Ulasi’s true passion was fiction. She wrote several popular “juju novels” – mysteries rooted in Igbo folklore and everyday life – with titles like Many Thing You No Understand (1970) and Who Is Jonah?. These novels were among the first by a Nigerian woman, and they proved that African English fiction could blend local dialects (she famously used Nigerian Pidgin in dialogue) with African themes. Literary critics call her work “Nigeria’s answer to the gothic and magic realism,” reflecting its unique style.

These three women are just the beginning, proof that Nigeria’s history is rich with fearless, brilliant, and trailblazing women who haven’t always gotten the recognition they deserve. But we’re not done yet. In the next part of this series, we’ll introduce even more phenomenal women whose stories continue to inspire and empower. So, stay with us as we uncover more legacies that deserve the spotlight and maybe even spark the fire in you to write your own chapter in history.