By Sunkanmi Adewunmi

Nigeria’s schooling system has seen waves of ambitious federal education policies – from Universal Basic Education (UBE) to JAMB admission rules and TETFund budgets – all promising a brighter future for our youth. In practice, the story is mixed. Universal primary enrollment has risen under UBE, but many children (about 10.5 million) still remain out of school. Free meals and “Safe School” programs can boost attendance, yet poor execution means many students still face hunger or insecurity on the way to class. Let’s break down the key reforms and see what they really mean for Nigerian students.

Universal Basic Education & Early Reforms

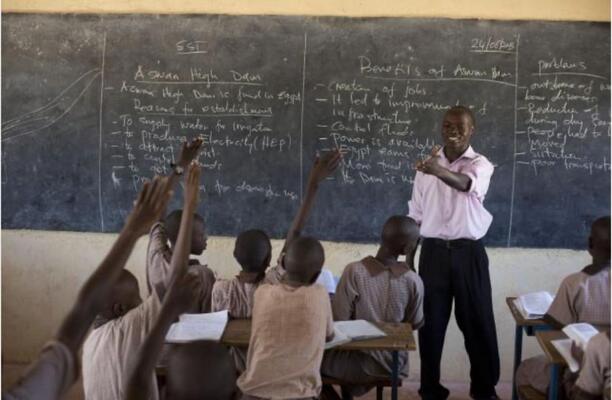

In the 1970s Nigeria revamped its system under the National Policy on Education, settling on the classic 6-3-3-4 model (6 years primary, 3 years junior sec, 3 years senior sec, 4 years university). Decades later the 2004 UBE Act was meant to guarantee free, compulsory schooling for ages 6–15. That push boosted enrollment. UNESCO reported secondary attendance soared 130% between 2000 and 2013 (though primary oddly fell by 4%).

More children are now enrolled in school, but overcrowding, poor funding, unqualified teachers, weak enforcement, and social barriers—especially for girls—continue to undermine education quality and leave many behind.

Curriculum Reforms: 6-3-3-4 to 12-4

To align with global standards, the FG has repeatedly reworked the structure. In 2025 it scrapped all junior and senior secondary levels, creating a continuous 12-year basic education model. The idea is to keep children in school longer (now up to age 16) and standardize the learning path. In theory, a 12-year cycle means one uniform curriculum nationwide. Officials argue this will reduce dropouts and introduce vocational training earlier.

Students now benefit from more years of learning and new skills, but the reform strains already-overcrowded primary schools and forces a rushed change of curriculum. In short, curriculum reform in Nigeria is still a work in progress.

School Feeding Program

The Home-Grown School Feeding Program (NHGSFP) provides a free meal to public primary pupils, tackling hunger and boosting attendance. It’s had both highs and lows. After NHGSFP’s 2016 relaunch, it served over 300 million meals to more than 7.5 million children by 2017, helping many kids come to class. (The program even sources food locally to support farmers.)

Implementation has faced setbacks. Under Buhari, the school feeding scheme was paused in some states due to complaints of poor-quality food and corruption—auditors even discovered ₦2.67 billion meant for feeding and textbooks diverted into private accounts. The good news is that budgets have since increased, but schools and families now hope the funds truly reach the pupils.

Tertiary Education: TETFund & Admissions

Federal universities like UNILAG reflect Nigeria’s growing higher-ed sector, supported by TETFund—a 2% education tax used for research and infrastructure. Schools misusing or under-spending funds now risk losing future support. Foreign postgraduate scholarships were also suspended in 2024 to focus on local programs. While TETFund has improved labs and libraries, funding remains uneven.

Meanwhile, JAMB raised the 2025 UTME cut-off to 150 and confirmed 16 as the minimum university entry age overturning a recent push to require 18. The goal is better-prepared students, though it adds pressure on families to plan earlier.

Challenges & Disparities

Across all levels, funding gaps and poor implementation limit impact. UNESCO notes Nigeria spends under 8% of its budget on education – far below the recommended 15–20%. The consequence: Nigeria still has about 10.5 million out-of-school children, mostly in the poorest states. Other persistent hurdles include:

- Underfunding: Free education policies often lack the budget to cover basics like classrooms, books, and teachers.

- Teacher shortage: Many teachers are under-qualified, hurting student performance. Training programs exist, but progress is slow.

- Corruption: Billions meant for feeding and materials have been diverted, and some TETFund grants go unused.

- Inequality: School quality varies by region—urban schools may have internet and libraries, while rural ones lack basics.

Even the best policies can flop when these gaps are ignored. A parent might hear of “free school” on TV, but find that in practice she still pays for uniforms or books.

Impact on Nigerian Youth

Recent federal education reforms in Nigeria have introduced technical skills training and digital learning platforms, improving access and career readiness for many students. However, significant challenges remain: overcrowded classrooms, funding shortfalls, and unequal admissions still affect millions. Efforts like Nigeria’s new digital learning platform and exam digitization aim to boost quality and transparency, but gender and regional disparities persist. While the reforms have expanded access and modernized learning, ongoing issues with quality and inclusion continue to hinder the daily experiences and future opportunities of Nigerian youth.

Nigeria’s education policies promise a lot—free schooling, school meals, safer campuses, and tech upgrades. While some students benefit from these reforms, issues like overcrowded classes, unpaid teachers, and broken promises still persist. Real change depends on proper execution. For policies to truly empower the next generation, citizens and educators must demand accountability, funding, and consistent follow-through.